Wednesday, November 2

Scots Confession

Patrick Hamilton and George Wishart first proclaimed the doctrines of the Reformation in Scotland. Both men were gifted scholars, beloved disciplers, and bold preachers. Both had been influenced by Martin Luther during studies abroad, both had benefited from William Tyndale’s translation work, and both were eventually martyred—Hamilton in 1528 and Wishart in 1546.

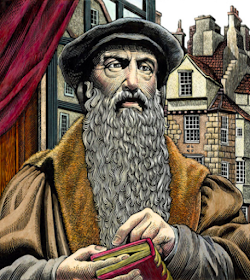

One of Wishart’s disciples, John Knox, was emboldened by the courageous life and death of his mentor. He determined to press forward the cause of Reformation in Scotland despite the obvious dangers. Through a dramatic series of events, including the assassination of the spiteful Bishop Beaton, the capture and barricading of the St. Andrew’s castle, and a subsequent siege by French war galleons, Knox was captured and made a galley slave. Upon regaining his freedom he studied under Calvin at Geneva, served King Edward at Westminster, prepared an English study Bible with Beza at Lausanne, and helped write a Book of Common Prayer with Bucer and Cranmer at Lambeth. But, always his heart was set on returning to Scotland. His persistent prayer was, “Lord, give me Scotland or I die.”

At last in 1559, Knox returned to his homeland. And despite fierce opposition from the crown and the nobility, he found the nation ready and waiting for Gospel reforms. With the death of the Queen Regent, Mary of Guise, in 1560, the Scottish Parliament convened in Edinburgh to address a host of issues confronting the restless nation.

In his History of the Reformation in Scotland, Knox gives a record of the extraordinary drama that soon unfolded. A supplication was laid before Parliament by a number of prominent Protestants, exposing the corruptions of the Scottish church. Evidence of the scandalous doings was overwhelming and undeniable. In response, Parliament beseeched the Protestants to draw up "in plain and several heads, the sum of that doctrine which they would maintain, and would desire that present Parliament to establish as wholesome, true, and only necessary to be believed and received within that realm."

Over the next four days, the Scots Confession was hastily drafted by Knox and five of his closest disciples and friends: John Winram, John Spottiswoode, John Willock, John Douglas, John Row (known as the “Six Johns”). On August 17, 1560, the document was read twice, article by article, during an open Parliamentary. Thereafter, the Confession was ratified with a near unanimous affirmation.

Composed in very economical prose and spanning just 25 articles or chapters, the Confession was warm, direct, humble, practical, and deeply devotional. Every proposition was accompanied by abundant Scripture references. As a result, it would prove to be a worthy a model for many of the creeds, confessions, and covenants that would follow in succeeding years.

The Church of Scotland would approve the Westminster Confession and Catechisms eight decades later; but the Scots Confession would remain its first, its dearest, and its most eloquent heart-cry of the faith that changed the whole course of the nation—and because of its profound influence on the Puritans in England and in America, the whole course of the world.

No comments:

Post a Comment